The story of public transit ballot measures in 2020 is counterintuitive. In more ways than we can count, 2020 was a catastrophe for nearly all sectors of society. Sadly, public transit was no exception. With large shares of Americans sheltering-in-place, transit ridership has plummeted — and with it, revenue for transit agencies.

However, in the face of those challenges, transit agencies and their dedicated workers rose to the occasion, finding new solutions to keep workers and riders alike safe from transmission while continuing their mission to transport essential workers to where they needed to be.

And many communities went a step further, asking voters through ballot measures to provide funding to either expand or keep pace with their mobility needs. By and large, voters responded.

In 2020, voters cast their ballots on 52 total public transit ballot measures and approved 47 pro-transit measures (a 90 percent win rate). Of that total, 15 of 18 ballot measures were approved on the November ballot, and 40 out of 43 measures passed during the covid-19 pandemic.

These measures will generate an estimated $753 million in new revenue annually and $17 billion in total revenue.

Despite the challenges the industry faced this year, voter support for public transportation has risen. The 90 percent win rate this year improved on our record in 2019 (80 percent), the last major election in 2018 (81.58 percent), and the last presidential election in 2016 (68.83 percent).

At face value, the overwhelming success of public transit ballot measures is surprising. But a deeper look at the measures collectively, and individually, shows how eager communities were for change.

The larger measures, like in Austin and Cincinnati, had spent years developing thoughtful, detailed policies, and equivalent time and energy building a broad-based coalition of stakeholders in support of their measure. We attribute their success to a number of factors, but in most cases, it can be distilled into a few core lessons:

- Planning. The most successful plans were detailed, multimodal, diverse infrastructure plans that also included housing and anti-displacement measures;

- Research. Communities conducted message and opinion research, gleaned important lessons from the data, and adhered to that data throughout the campaign;

- Discipline. Despite the inevitable distractions in the later stages of a campaign, successful measures adopted a strategy and message framework, and stuck to it.

Another noteworthy trend of the 2020 cycle was the outward progressive bent assumed by many of the campaigns. They adopted messages about environmental sustainability and social equity, frames that had often been relegated to second-tier or constituent specific campaign materials. Messages about job creation were still featured but were not incorporated as much into media targeting persuasion and mobilization audiences.

This message frame is a response to several factors. First, campaigns conducted the message and polling research to determine what messages moved their targeted voter universe. These voters, in many cases, came from communities of color who would benefit directly from expanded and improved service and were included in campaigns’ targeted universe. Second, and related, was the broader atmospherics and political currents largely spurred by the Black Lives Matter movement and calls for police reform.

These factors created the political space for campaigns to talk about transit as a solution to equity. Campaigns, and local leaders, were able to position themselves as leading the next frontier in a national social justice movement by championing a cause that would help communities of color lift themselves up.

Despite the progressive orientation of the campaigns in 2020, most still enjoyed the bi-partisan, and business, support public transit traditionally enjoys. Indeed, the Cincinnati Chamber of Commerce spearheaded its ballot measure and measures in Seattle, Austin, and San Antonio all engendered strong support from the business community. Portland was the most noteworthy outlier. Led by Nike’s $915,000, the business community opposed Portland measure 25-218, largely because they were against the payroll tax that would have funded the measure.

Throughout 2020, CFTE has been keen to tell the story of public transit. Despite the dire financial situation the pandemic has leveled on the industry, we see inspiration and a story of perseverance. The takeaways contained below come not only from our external analysis of the measures, campaigns, and results, but also from CFTE’s on-the-ground experience assisting the campaigns for many of this year’s biggest and most innovative measures.

The Covid-19 Pandemic and Campaign Messaging

There were several shifts in message during the 2020 campaign, including two in particular: a focus on essential and frontline workers; and, a notable bend to the left.

Campaigns’ focus on frontline and essential workers was significant for a variety of reasons. First, there was nothing abstract about the connection. Put simply, public transit moved nurses and grocery workers to their jobs, which kept us healthy and fed. It wasn’t abstract or theoretical policy. Public transit’s role was tangible and cherished, which led to a reservoir of public goodwill.

Here is an example from the Let’s Get Moving campaign in Portland, OR.

In virtually all major battlegrounds, voters recognized the importance of public transportation during the pandemic. In the short-term, this campaign yielded positive results. But we speculate that this moment seeded more enduring sympathies toward public transportation.

In recent years, the industry has debated and toiled over the question of how to connect with non-riders. While we don’t yet have the hard data, the story of essential and frontline workers has been a perfect illustration.

Even though you’re staying home and staying safe, your nurses and doctors are going to work to make sure you’re staying healthy — and public transportation gets them there.

Equity in Plans and in Messaging

This cycle saw campaigns put a focus on highlighting specific ways their plans would help underserved populations. Racial equity was a particularly salient topic, but arguments about how transit serves youth, seniors, and disabled people were also popular.

Racial equity was a large part of the planning process for these measures, as agencies made sure their plans provided service in previously underserved parts of their communities and included programs for low-income riders. Not only did they incorporate equity into their plans, but transit agencies also made a point of publicly elevating that aspect of their plans.

Beyond the plans themselves, equity was also a more salient message than it has been in past cycles — this was reinforced through survey research.

Interestingly, the Prop A campaign in Austin found that racial equity was not a principal message in its initial polls earlier in the cycle but the issue became one of the most salient messages later in the summer. This trajectory aligned with national events, including the beginning of the covid-19 pandemic and the protests around the death of George Floyd.

Above: Examples of equity messaging from 2020 campaigns in Portland (left) and Seattle (right)

Environmental Sustainability

Conservation and sustainability have always been central to public transit’s appeal, even more so in 2020. Certain communities, like Seattle and Portland, also found that messaging around climate change was more salient than in previous cycles.

Above: Examples of environmental messaging from 2020 campaigns in Portland (left) and Austin (right)

That said, climate change was not a top polling message across the board. For example, San Antonio found in polling that climate change was not as persuasive and it was not heavily incorporated into their messaging.

Transit Agency Image, Central to Success

One thing we know about any campaign is that the messenger is often as important as the message. In this case, the image and public trust engendered by the transit agency and other government agencies was important to measure success.

While election firewalls generally prevent agencies from weighing in on the campaign, their public image is a factor. Agencies became a point of criticism for opposition campaigns and an agency that is well trusted can mitigate those concerns and bolster their campaign.

This is yet another example of the success story of Austin’s Capital Metro. In 2014, transit advocates lost a ballot measure campaign that some local officials attribute, in part, to a low level of trust in Capital Metro at that time. In the intervening years, Capital Metro has worked assiduously to improve its image and service.

And… mission accomplished. This cycle, polling showed Capital Metro was one of the most trusted messengers for Prop A, polling even higher than the popular mayor, Steve Adler (who also polled very well). The work the agency did was critical to the measure’s success.

Central Opposition Messaging Themes

Organized opposition heavily relied on anti-tax arguments this cycle. It was a remastered version of the same ‘ole country song: Now is the wrong time for new taxes, featuring covid-19. However, anti-light rail rhetoric still popped up in both Austin and Portland.

Opposition to Regressive Funding Mechanisms

This year, we saw a greater opposition to funding mechanisms that are considered “regressive” because they fall more heavily on lower-income segments of the community. This opposition was largely present in more Democratic-leaning areas and while it was not enough to defeat most measures, arguments related to this are growing and will increasingly be a challenge for campaigns.

Seattle, WA

The Prop 1 campaign in Seattle faced its main opposition on the grounds that a sales tax was regressive. The campaign was able to succeed with an overwhelming majority by countering this argument with other, equity-focused features of the plan.

Bay Area, CA

While a planned mega-measure was ultimately not put on the ballot for November in the Bay Area due to the covid-19 pandemic, it is still being planned for a future year. The measure, however, had some internal division: Faster Bay Area was pushing a sales tax plan, while Voices for Public Transportation (different than the APTA-aligned grassroots organization with the same name) was pushing for a different funding mechanism on the grounds that a sales tax was regressive. The delay in the measure has given advocates a chance to bridge the gap between the two plans.

Portland, OR

While Measure 26-218 was not funded by a sales tax, the Stop the Metro Wage Tax campaign framed the tax as regressive and falling more heavily on employees to gain traction with more left-leaning voters.

Above: A graphic released by the Stop the Metro Wage Tax campaign opposing Measure 26-218

In our opinion, the Stop the Metro Wage Tax campaign approach was bad faith and misleading. Measure 26-218 delayed the tax increase until 2022 so as not to compound the negative impact of covid on the economy.

Gaining Ballot Approval

In several communities last year, voter approval was not the most insurmountable hurdle. Instead, it was getting a measure on the ballot in the first place. This was true for several reasons, namely in light of the covid-19 pandemic.

In Lucas County, OH, just one of the communities needed blocked the proposal to put a sales tax measure on the ballot for TARTA, stopping the measure in its tracks. In Florida, discussion of a back-up transportation tax was stalled until 2021 against the wishes of advocates.

After a lengthy fight to get on the ballot due to internal city politics, a sales tax for VIA Metropolitan Transit in San Antonio passed somewhat easily.

How Transit Fared vs. Other Items on the Ballot

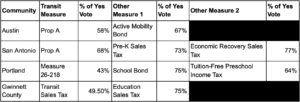

Austin, TX

In Austin, TX, a second transportation measure, Prop B, was also on the ballot. This bond measure was created to fill gaps in Prop A and spend money on connectivity, walkability, bikeability, and other non-transit, but related priorities that were not included in Prop A. With a smaller campaign but also a quieter opposition, Prop B outperformed Prop A, winning 67 percent of the vote to Prop A’s 58 percent.

San Antonio, TX

In San Antonio, TX, two other tax measures were on the ballot. One, Prop A, reauthorized a ⅛ cent sales tax to fund pre-K education. The other, Prop B, was a temporary measure to use the ⅛ cent sales tax sought by VIA Metropolitan Transportation for economic recovery before VIA’s measure would activate the tax in 2025. Both measures outraised the transit measure, making the fundraising and campaigning environment difficult for that measure. Prop A received 73 percent of the vote while Prop B received 77 percent, both outperforming the transit measure’s 68 percent of the vote.

Portland, OR

In Portland, OR, four other tax measures appeared on the ballot, including a library bond, parks and rec levy, an income tax for tuition-free pre-school, and a school bond. All four measures passed with 60 percent of the vote or more. The school bond, the highest-profile of these measures, enjoyed strong financial support from the corporations that opposed Measure 26-218.

Gwinnett County, GA

In Gwinnett County, where a transit sales tax failed by less than one percent of the vote, another sales tax measure for education was on the ballot and passed with 75 percent of the vote.

Conclusion

Passing a public transportation ballot measure is never an easy path, but 2020 presented additional challenges that none of us could have imagined. Faced with a global pandemic, a crowded election cycle, a tough fundraising environment, and all of the challenges and opposition that already come with trying to pass a transformational measure, it was easy to believe that asking voters to invest in the future of their transportation systems was a nonstarter. But in the face of that, many communities decided that there wasn’t time to wait to invest in transportation. And their efforts paid off.

Thanks to the tireless efforts of advocates, 47 communities all over the country will see new funding for public transportation due to measures passed in 2020. The success of these measures confirmed so much of what we already knew: that transit is popular in America; that voters will entrust their money to strong elected leaders and transit agencies that have earned their trust; and, that transit brings together diverse coalitions of unlikely allies.

Additionally, advocates showed a willingness to adapt. We talked about equity, the environment, and recovery from the pandemic, and we backed it up with innovative, well-designed strategic plans.

Campaigns told the story of public transportation’s role to make communities go — and voters responded.

With the vaccine rollout underway, the pandemic’s end in sight. But the scars left on our communities, and particularly our transit systems, will not just fade away. Transit funding is more of a priority than ever, and CFTE expects to see many more communities go to the ballot with funding measures in 2021 and 2022. We are excited to learn from the success of this year’s measures to keep advocating for public transportation in the coming years.

Please be in touch if your community is considering a measure. Stay safe and good luck.